Wpi Summer Camps Video Game Design

When 12-year-old Katie Foti showed up for her first day of Girls Make Games camp this summer, she thought she knew what creating a video game was all about.

"I thought it was just like, 'You code some stuff, you make some art,'" said the homeschooler from Brandon, Florida. "Boom—you're done."

By the end of the three-week session, she had to admit: "It's not that simple."

Digital games, of course, have provided entertainment and comfort to millions during the pandemic. This summer, as young people took a much-needed break, educators turned to game design to provide a dose of critical thinking, planning, and project-based STEM work to students who have had little of any of this since the start of the pandemic.

The eight-year-old program, exclusively online for the past two years, takes the basic idea of coding, team-building, and design camps and adds a dash of girl power, bringing together young women who, by their own admission, are often the only girls they know who like video games. Most arrive at the first day of camp with limited coding experience and leave with a completed video game.

The idea originated with Laila Shabir, an MIT finance graduate whose experience growing up in the Middle East taught her that society's expectations for young women can have a profound impact on how they see themselves as both students and professionals.

Born in Pakistan, Shabir spent her childhood in the United Arab Emirates, where her father worked as a laborer. She spent her formative years fighting against a bias in her own culture that discouraged women from getting an education. She recalled "just being constantly reminded and painfully aware of being a girl, and what kind of possibilities my life would hold."

But her parents valued education, and urged her to work hard. From the time she was in second grade, she ran her own after-school homework help program for schoolmates. Her parents encouraged her to apply to top colleges in the U.S., and she ended up at MIT. She laughs now, recalling that she thought it was just another college. "When I was applying, I didn't know it was that big a deal," she said.

Shabir earned a degree in finance, but found she was more interested in teaching.

While preparing to apply to a teacher prep program, she met her future husband, a mathematician who played the first-person shooter game Halo "somewhat competitively," she recalled. "And I was just so shocked because if I ever talk to him, I would never, never assume that this is someone who's so passionate about video games. He's a mathematician. He talks about all these great concepts. And my idea of a gamer was your standard stereotype: living in mom's basement."

They eventually hatched an idea for a company that would combine their talents to create educational games. But when they began recruiting employees, only male candidates applied. "I was just like, 'I don't understand. I can't be the only girl'" interested in games.

She soon realized that, just like her experience with mixed messages about education growing up in the UAE, girls in the USA were hearing similar, more "subliminal" messages about the games they loved.

A 'social experiment'

Like many tech-facing fields, game development has long suffered from a dearth of female talent, for various problematic reasons: impossibly long hours, a male-dominated workforce that's often hostile to women, and office cultures that turn a blind eye to sexual harassment.

In 2014, Shabir started Girls Make Games—as a kind of "social experiment."

"I wanted to meet girls who identified as gamers and understand why they like games, or what could we do to get more girls interested in games," she said. They held three small sessions in California, Seattle, and Austin, Texas—with a total of about 115 girls.

That was eight summers ago. Since then, nearly 6,500 girls have completed the program, with about 20,000 using its online resources. Campers pay $1,000 for the three-week course, but the organization also provides need-based scholarships of up to 100 percent of tuition. The camp boasts that it has never turned away an applicant.

Each year, Shabir typically picks another city to host the three-week camp, which tasks every girl, usually working in teams, with creating an original game.

The camp not only promotes a message of empowerment for girls, but one that encourages them to think differently about games. Shabir urges campers to "think big" about games and get to the essence of the games they love and why they love them. Each summer, she also brings in developers from big game studios and other "top minds in the industry" to serve as role models. The program's unofficial motto takes the form of a question: "Does the world need this game?"

Most summers, campers collaborate to figure out the process of building characters, levels, and other elements, all within the confines of a prefab game engine. In the process, they learn not only negotiation skills but how to use their devices—typically Chromebooks, iPads, and the like—for something more than just consuming media. But even now she fights against the stereotype of gamers as young men. "It's still a persistent problem," she said. "The only place where they're surrounded by kids who look like them is at Girls Make Games."

In the past, girls have occasionally signed up for the camp, only to drop out at the last minute with "the jitters" before the session begins. "They're so sure that they're going to be bad at it, because it feels like something that girls don't do."

The answer: Surround them with other girls who are "just as nerdy" as they are and give them a place to indulge their love of games—as well as the space to work intensively on an original idea.

A few titles have even found modest commercial success: In 2019, a group of middle-school campers designed What They Don't Sea, a marine-themed exploration game that has raised more than $40,000 on Kickstarter. Another, Interfectorem, also created by a middle-school team, is available on Sony's PlayStation Store.

As with other educational efforts, the pandemic in 2020 forced Shabir to move the entire endeavor online. The move turned out to be a blessing in disguise, opening the program up to a global audience. Over the past two summers, about 2,000 girls have attended worldwide. This summer, students from 10 countries and 79 cities showed up, virtually all of them telling the same story of isolation and exclusion in their passion for video games.

Among them was Katie, the Florida homeschooler, who loves art, but, she realized, had a lot to learn about game design. Among her biggest challenges: making the game accessible for everyone, even players with disabilities—often accomplished by providing keyboard shortcuts or other methods to make the game playable, for instance, by players with visual, auditory, or motor challenges. "I didn't realize that was a thing you had to do," she said.

She also didn't appreciate how hard it'd be to make the art look good. "It's really difficult," she said.

Shabir said many students arrive at camp with a great story idea, "but there's really no game to it." To turn it into a game, she said, they must impose a set of rules on their imaginary world.

Her experience this summer has made Katie think about game design as "something I want to do as part of my career," though she also might like to make a living streaming her gameplay on YouTube.

As a longtime homeschooler, Katie saw less of a disruption than most students last year, but the pandemic did knock out a beloved homeschoolers' dance class that provided a rare opportunity for her to mingle with peers. There was a Zoom version, she said, but "it was a little bit weird, though, because I had to do it in the middle of my living room." She skipped it.

Mostly the pandemic kept her and other local homeschoolers isolated and apart. "I was stuck inside of the house with my brother," she said. "And I'm pretty sure you can imagine that probably wasn't fun."

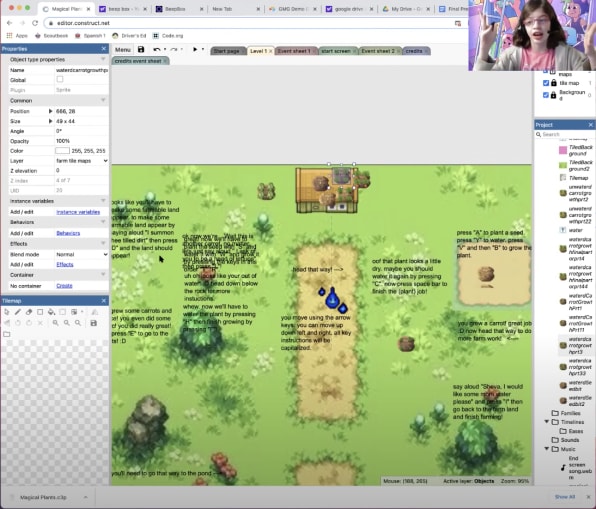

When the camp's three weeks were up, she had a game: Magical Plants, a farming game that she calls "Stardew Valley meets Animal Crossing meets Minecraft." Stardew Valley, while not as well-known as the other two titles, is an open-ended simulation game that allows players to grow crops, raise livestock, and interact with characters in a fictional farm town.

"I like peaceful games," she said, "and I feel like there are not enough of them out in the world yet. So I made another."

A 'third space' for play

Experts say game design scratches an important itch: Learning how games work not only makes young people better media consumers, it also gives them tools for understanding an important media form that will become increasingly more important in the future. They must learn not only about how games thrill us, but also how they shape our behavior—often for the developer's benefit.

"To be literate in the 21st century is to really understand how those systems work," said Matthew Farber, an assistant professor of education at the University of Northern Colorado and founder of its Gaming SEL Lab.

Farber, who is also the author of the recent book Gaming SEL, said many popular games replicate a key element that kids are missing: the kind of play that takes place during recess.

His 10-year-old son and the boy's friends spent a lot of time this year in Minecraft, Farber said, and they hacked another digital tool to make it even more fun.

"Because they were learning in Zoom, they sent each other Zoom links, and they would play hide-and-seek in Minecraft with the Zoom audio open," he said. "So they were really using the tools themselves to create a 'third space' for play, because they couldn't physically always go to each other's houses and do things you would normally do in childhood."

That kind of innovation and self-expression, he said, is key to games. "Really the goal is sharing with others," he said. "And that is a lot of what Girls Make Games does."

As more female game designers enter the industry, Shabir said, the camp's impact will be felt more widely. In fact, the camp has seen so much interest in young women wanting to enter the industry that it created its own fellowship program. Campers who age out of the program return as teachers.

Kayla Derilus attended in 2015, the summer before her freshman year of high school in Durham, North Carolina. That year, the camp took place in its hometown of Raleigh, North Carolina, just a few miles away.

"It was really cool to see a lot of other girls playing games," she said. "That was the main thing that I took away from it—and the fact that I could actually make games, because I grew up with my uncles and my dad playing video games."

The experience prompted her to return the following year, and to take up coding. She never looked back. Now 19, Derilus is a rising junior at William Peace University in Raleigh, majoring in simulation and game design. She also taught at the camp this summer, and said her young students—most of them 8 or 9 years old—needed one key thing: "Someone who was always there."

Derilus took her summer office hours very seriously.

"I feel like online, it's very easy to tap out," she said. "I saw with some of my professors, they were just like, 'All right, we're done.'"

Derilus said she'd often stick around after class to take questions, "just to engage with them as well—just being there for them."

The past two summers have been a kind of watershed moment for the camp. Before Shabir and her colleagues made the jump to Zoom, reaching campers in 10 countries and 79 cities simply wasn't an option.

Eight years in, Shabir often feels "that we just got started" in her social experiment. "There's so much work to be done, and there's so many kids that need this."

Over the next couple of years, she said, her first few "fellows," such as Darilus, who attended as middle-schoolers and taught younger students as high-schoolers, will begin graduating from game design programs themselves, starting careers as full-time developers—all because of a summer camp.

"There's a couple that are going to start jobs next year," she said. "We're nearly there."

This article was also published at The74Million.org, a nonprofit education news site.

Wpi Summer Camps Video Game Design

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/90670105/girls-make-games-summer-camp

Posted by: thompsonwhirds.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Wpi Summer Camps Video Game Design"

Post a Comment